|

|

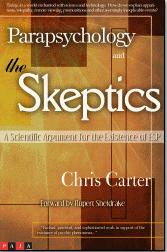

Parapsychology and the Skeptics

|

|

Originele titel: A Scientific Argument for the Existence of ESP

Chris Carter

|

Type:

|

Paperback

|

|

Uitgever:

|

|

|

Gewicht:

|

510 gram

|

|

Aantal Pagina's:

|

320

|

|

ISBN:

|

15-8501-108-8

|

|

ISBN-13:

|

978-15-8501-108-7

|

|

Categorie:

|

Parapsychologie

|

|

Richtprijs:

|

€ 19,95

|

Korte Inhoud

The scientific evidence for life after death

• Explains why near-death experiences (NDEs) offer evidence of an afterlife and discredits the psychological and physiological explanations for them

• Challenges materialist arguments against consciousness surviving death

• Examines ancient and modern accounts of NDEs from around the world, including China, India, and many from tribal societies such as the Native American and the Maori

Predating all organized religion, the belief in an afterlife is fundamental to the human experience and dates back at least to the Neanderthals. By the mid-19th century, however, spurred by the progress of science, many people began to question the existence of an afterlife, and the doctrine of materialism--which believes that consciousness is a creation of the brain--began to spread. Now, using scientific evidence, Chris Carter challenges materialist arguments against consciousness surviving death and shows how near-death experiences (NDEs) may truly provide a glimpse of an awaiting afterlife.

Using evidence from scientific studies, quantum mechanics, and consciousness research, Carter reveals how consciousness does not depend on the brain and may, in fact, survive the death of our bodies. Examining ancient and modern accounts of NDEs from around the world, including China, India, and tribal societies such as the Native American and the Maori, he explains how NDEs provide evidence of consciousness surviving the death of our bodies. He looks at the many psychological and physiological explanations for NDEs raised by skeptics--such as stress, birth memories, or oxygen starvation--and clearly shows why each of them fails to truly explain the NDE. Exploring the similarities between NDEs and visions experienced during actual death and the intersection of physics and consciousness, Carter uncovers the truth about mind, matter, and life after death.

Uittreksel

Foreword - by Rupert Sheldrake, Ph.D.

This is an important book. It deals with one of the most significant and enduring fault-lines in science and philosophy. For well over a century, there have been strongly divided opinions about the existence of psychic phenomena such as telepathy. The passions aroused by this argument are quite out of proportion to the phenomena under dispute. They stem from deeply held world-views and belief systems. They also raise fundamental questions about the nature of science itself. This debate, and the present state of parapsychology are brilliantly summarized in this book. Chris Carter puts his argument in a well-documented historical context, without which the present controversies make no sense.

The kind of skepticism Carter is writing about is not the normal healthy kind on which all science depends, but arises from a belief that the existence of psychic phenomena is impossible; they contradict the established principles of science, and if they were to exist they would overthrow science as we know it, causing chaos and confusion. Therefore anyone who produces positive evidence supporting their reality is guilty of error, wishful thinking, self-delusion or fraud. This belief makes the very investigation of psychic phenomena taboo and treats those who investigate them as charlatans or heretics.

Although some committed skeptics behave as if they are engaged in a holy war, in this debate there is no clear correlation with religious belief or lack of it. Among those who investigate psi phenomena are atheists, agnostics and followers of religious paths. But the ranks of committed skeptics also include religious believers, agnostics and atheists.

As Carter shows so convincingly in this book, the question of the reality of psi phenomena is not primarily about evidence, but about the interpretation of evidence; it is about frameworks of understanding, or what Thomas Kuhn, the historian of science, called paradigms. I am sure Carter is right.

I have myself spent many years investigating unexplained phenomena such as telepathy in animals and in people. At first I naively believed that this was just a matter of doing properly controlled experiments and collecting evidence. I soon found that for committed skeptics this is not the issue. Some dismiss all the evidence out of hand, convinced in advance that it must be flawed or defective. Those who do look at the evidence have the intention of finding as many flaws as they can, but even if they can’t find them; they brush aside the evidence anyway, assuming that fatal errors will come to light later.

The most common tactic of committed skeptics is to try to prevent the evidence from being discussed in public at all. For example, in September 2006, I presented a paper on telephone telepathy at the Annual Festival of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. Our controlled experiment had shown that people could, before answering the phone, correctly identify who was calling (from a choice of four people) over 40% of the time, when a success rate of 25% would be expected by chance alone. The following day, in The Times and other leading newspapers, several prominent British skeptics denounced the British Association for “lending credibility to maverick theories on the paranormal” by allowing this talk to take place. One of them, Professor Peter Atkins, a chemist at Oxford University, was quoted as saying, “There is no reason to suppose that telepathy is anything more than a charlatan’s fantasy.” (The Times, September 6, 2006). Later the same day, he and I took part in a debate on BBC Radio. He dismissed all the evidence I presented as “playing with statistics”. I then asked him if he had actually looked at the evidence, and he replied, “No, but I would be very suspicious of it”.

As Carter shows, conflicts about frameworks of understanding are inherent within science itself. Since its beginnings in the sixteenth century, science grew through a series of rebellions against established worldviews. The Copernican revolution in astronomy was the first. The mechanistic revolution of the seventeenth century, with its dismissal of souls in nature, as previously taught in all the medieval universities, was another great rebellion. But what started as rebel movements in turn became the orthodoxies, propagated by scholars, and taught in universities. Subsequent revolutions, including the theory of evolution in the nineteenth century, and the relativity and quantum revolutions in physics of the twentieth century again broke away from an older orthodoxy to become a new orthodoxy in turn.

There is a similar tension within the Christian religion, which provided the cultural background to the growth of Western science. Christianity itself began as a rebellion. Jesus rejected many of the standard tenets of the Jewish religion into which he was born. His life was one of rebellion against the established religious authorities, the scribes and Pharisees, the chief priests and the elders. But the religion established in his name in its turn became orthodox, rejecting and persecuting heresies, only to be disturbed by further rebellions, most notably the Protestant Reformation. In the debate that Carter documents, the skeptics are the upholders of the established mechanistic order, and help maintain a taboo against “the paranormal”. They come in various kinds, and it would probably not be too difficult to find parallels to the chief priests and elders, concerned with political power and influence, and to the scribes and Pharisees, the zealous upholders of righteousness.

This struggle has a strong emotional charge in the context of western religious and intellectual history. But now, in the twenty-first century, there are many scientists of non-western origin, including those from India, China, Africa and the Islamic world. Western history is not their history, nor are the strong emotions aroused by psi phenomena ones with which they can easily identify. In most parts of the world, even including western industrial societies, most people take for granted the existence of telepathy and other psychic phenomena, and are surprised to discover that some people deny them so vehemently.

From my own experience of talking to scientists and giving seminars in scientific institutions, dogmatic skeptics are a minority within the scientific community. Many scientists are curious and open-minded, if only because they themselves or people they know well have had experiences that suggest the reality of psi phenomena. Nevertheless, almost all scientists are aware of the taboo, and the open-minded tend to keep their interests private, fearing scorn or ridicule if they discuss them openly with their colleagues.

I believe that for the majority of the scientific community, in spite of the appearances created by vociferous skeptics, what counts more than polemic is evidence. In the end, the question of whether or not psi phenomena occur, and how they might be explained, depends on evidence and on research.

No one knows how this debate will end or how long it will take for parapsychological investigations to become more widely known and accepted. No one knows how big a change they will make to science itself, or how far they will expand its framework. But the conditions are good, and an intensifying debate about the nature of consciousness makes the evidence from parapsychology more relevant than ever before.

This is one of the longest running debates in the history of science, but changes could soon come faster than most people think possible. Parapsychology and the Skeptics is an invaluable guide to what is going on. It is essential reading for anyone who wants to be part of a scientific revolution in the making.

Recensie

door

Tsenne Kikke

I've always thought that if the existence of psi becomes generally recognised, the sceptics would indirectly have a lot to do with it. As the scientific case for it gradually builds, the angry agit-prop of old guard types like Martin Gardner and James Randi seems ever more irrelevant. Generalisations that parapsychology is a pseudo-science, there is no evidence, Hume's argument against miracles, etc, still have some force. But critics like Ray Hyman, Susan Blackmore and Richard Wiseman are also having to come up with specific objections to psi experiments, and in a few cases doing experiments themselves.

So the time is ripe for giving these counter-arguments some close scrutiny. In fact I'm surprised it is not done more often, as many of them are so obviously specious. Of course researchers such as Dean Radin and Rupert Sheldrake have focused on this to some extent - Radin has a useful chapter on it in The Conscious Universe - but it's far from being their main focus. I think this has been a weakness for parapsychology as a whole, that the sceptics have managed to get away with too much for too long.

Chris Carter's Parapsychology and the Skeptics: A Scientific Argument for the Existence of ESP is arguably the first major attempt to place the sceptics' arguments in their proper context. It's an important book, and should be on everyone's reading list who is serious about understanding the issues.

A brief look at some nineteenth century work with mediums sets the scene, with the examples of investigations of Henry Slade leading into more modern controversies. A description of CSICOP follows, and the disagreements over its early activities. Carter goes on to discuss J B Rhine's work at Duke, PK experimentation, the Ganzfeld debate, and Sheldrake's research of a telepathic dog. Many notorious episodes are here, for instance the attempt by sceptical members of a National Research Council committee to stop a fellow member presenting evidence supporting the ganzfeld claims, and the failed attempt to get parapsychologists chucked out of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Also other dishonest shenanigans, like Randi pretending he had debunked doggy telepathy, when by his later admission he had nothing of the sort.

The book is chock full of quotes both from the sceptics and sympathetic scientists, which brings us closer to the debate, and often leaves one gasping with disbelief (the statement that there is nothing to argue about as there is 'no evidence of anything paranormal', here voiced by psychologist Nicolas Humphrey, is a particular head-scratcher).

I was expecting rather more space to be given to analysis of individual experiments: there is only a brief mention of the Stargate remote viewing programme, ditto on Sheldrake's highly suggestive work on the sense of being stared at and other of his research, the PK work by Jahn and Dunne at Yale, and so on. But I think Carter is right not to try to be comprehensive, and to leave plenty of space for dealing with the more general aspects of the critics' arguments.

For me this is actually where Carter is best, demolishing the scientific and philosophical objections to psi. As he points out, sceptics such as Blackmore like to say that it is incompatible with 'our scientific worldview', but this begs the question, which scientific worldview, the old one based on Newtonian mechanics and behaviourist psychology, or the emerging one based on quantum mechanics and cognitive psychology. Quantum non-locality and the view that consciousness, not measurement, is implicated in the collapse of the state vector both support the existence of psi and might even lead to predictions of it. The conclusion, Carter argues, is that the term 'paranormal' is an anachronism and should be dropped, as psi does not operate outside nature.

I was particularly interested in his nuanced discussion of Benjamin Libet's finding that brain activity precedes a conscious decision, which is routinely presented by sceptics, in their dull way, as 'another nail in the coffin for dualism' (Blackmore, Dying to Live, p. 237), and which of course is open to contrary interpretations, as Libet himself pointed out. Wilder Penfield's experimental findings on the neurological basis of memory is also used by sceptics in an anti-dualist sense which Penfield himself did not endorse.

No book is perfect, and I did have a slight quibble with the way it was structured - it seemed to jump around a lot between historical periods, types of experiments, supporters and critics, and so on. Having said this, I know from my own experience of trying to write about parapsychology how challenging it is to organise so much material. Nor does it detract from the book's value. Carter explains that he originally tackled the subject in its entirety, but the result was so massive it had to be broken down into three parts: the next instalment will be on survival evidence and the sceptical objections.

I suspect that in taking the debate directly to the sceptics Carter is first onto what may soon be a well-populated field. The enthusiasm for psi research in the 1960s and 70s led to a backlash over the next two decades with the founding of CSICOP, but there are signs that the sceptics may be running out of steam - the imminent suspension of Randi's prize being just one example. We may soon start to see the pendulum shifting the other way, and this time it is the nay-sayers who will be on the defensive.

- Robert McLuhan -

|